You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘São Paulo’ tag.

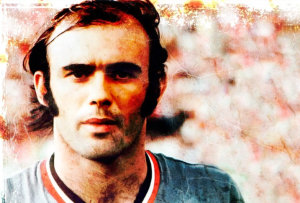

It is unfortunate that Waldir Peres, the Brazilian goalkeeper who died on Sunday aged 66, will be remembered mostly for his calamitous mistake in the 1982 World Cup match against the USSR.

Arquivo Histórico do São Paulo FC

Peres let Andrei Bal’s 30-yard strike squirm through his hands and the image became an unforgettable one for fans, particularly those outside Brazil, who thought of Brazilian goalies as no less dodgy than Scottish ones.

Peres was widely seen as the weak link in that star-studded team, alongside misfiring centre forward Serginho.

But Peres’ team mates did not agree with that assessment.

Sócrates was not close to Peres, who was older than he was and as a happily married homebody, not part of Sócrates’ drinking circle. The two also differed over Corinthians Democracy, with Peres and his team mates at São Paulo often dismissive of what they considered a distraction to the sole issue of playing football.

But Sócrates refused to condemn Peres for his mistake or single him out as a weak link. He pointed out that Peres was the best keeper in Brazil in the lead up to the 1982 World Cup and deserved his place.

Most notably, he had proved his worth in the 1981 mini-tour to Europe. Brazil beat France, West Germany and England and Peres was a factor in all three.

He saved not one but two penalties from Paul Breitner in the 2-1 win over West Germany that cemented Brazil’s position as favourites to lift their fourth World Cup title a year hence in Spain.

He was then excellent in the 1-0 victory over England at Wembley, a victory notable as the first time England had ever lost to a South American side at home.

Peres got his spot in fortunate circumstances, after first-choice stopper Carlos injured his elbow in the Mundialito tournament in Uruguay. Peres stepped in and helped Brazil to the final, defeating West Germany 4-1 in the process, before losing to the hosts.

But his performances helped cement his place, as did his personality.

He was quiet and serious and easy to get along with, unlike Emerson Leão, his other main rival for the No. 1 shirt. Leão had been first choice in 1974 and 1978 but seemed to enjoy rubbing people up the wrong way and coach Telê Santana refused to pick someone who would so obviously endanger the bubbly spirit in what was a settled and contented side.

After that early error against the USSR, Peres composed himself and performed well. He had little do against Scotland or New Zealand and was reliable in the 3-1 win over Argentina in the second round.

He was also blameless in the fateful 3-2 loss against Italy. Brazil went out not because of goalkeeping errors but because they kept trying to win a game they only needed to draw. They were exposed at the back and only the harshest of critics could fault him for any of Paolo Rossi’s three goals.

Unfortunately for Peres, those incidents are forgotten now. But the facts speak for themselves. He won the Brazilian league title with São Paulo and three Paulista state championship medals. Only one player in the clubs history has more appearances that he has.

He is fondly remembered at São Paulo. He deserves to be known elsewhere for more than that one mistake.

In a country where almost everything is maddeningly expensive, one of the highlights of traveling is the stop at Duty Free on the way home.

In a country where almost everything is maddeningly expensive, one of the highlights of traveling is the stop at Duty Free on the way home.

In Brazil that means Dufry, the company with the contract to sell duty free items at Brazil’s airports.

I’ve long suspected that Dufry are ripping people off, much like Itau, whom I wrote about here last year.

My suspicions were aroused a couple of years ago. I forgot my headphones when heading to the US and bought a pair in duty free at Guarulhos airport. A day or so later I spotted the same pair in a store in Florida for almost half the price.

When I came back to Brazil I asked Dufry for an interview but their press officer said it wasn’t the right time to talk. A few weeks later his boss was in Folha boasting about how the firm was thinking of opening stores on Brazil’s land borders.

I came back to Brazil again this week and found one more example of how Dufry are ripping off unsuspecting customers.

A bag of 25 two-finger Kit Kats was on sale at the Dufry shop for 54 reais. That works out to be 1.08 reais per finger. It seemed expensive so when I got back to Sao Paulo I checked out the prices.

I picked up a four-finger Kit Kat at a pharmacy in Sao Paulo yesterday for 3.50 reais, or 0.875 reais per finger. Much cheaper than in Dufry’s duty free shop.

Remember the whole point of a duty free shop is that the items they sell are tax free and so should be cheaper than in regular stores.

It’s hard to look at Dufry and see a company that is willfully ripping off its customers.

The protesters who took to the streets of Brazil’s biggest cities last night are to be congratulated on a significant victory.

Few people imagined that after the violent police crackdown on Sao Paulo’s protesters last Thursday an even greater number would come out in sympathy just four days later.

But they did just that and across Brazil hundreds of thousands of people, most of them peacefully, expressed their dissatisfaction with the status quo.

Exactly how many people took part in the protests is impossible to know. But estimates suggest 65,000 people took to the streets of Sao Paulo, almost twice that in Rio and smaller, but still considerable, numbers made their presence felt in Belo Horizonte, Salvador, Porto Alegre and dozens of other towns and cities.

The big question is what happens now. The protesters have the wind at their backs, so what will they do? They have called another march (in SP at least) for Tuesday night. Will they call more? Enter in to talks with authorities? As yet no one knows.

A lot of that depends on exactly what they want.

The unrest was originally sparked by a hike in bus fares and many of the protesters come from the Free Fare Movement, a group that wants free public transport for all. That’s an unreal demand. No serious country provides all its citizens with free public transport.

But since then the demonstration has expanded to include broader issues. One major complaint is the cost of hosting the World Cup and the Confederations Cup, the second of which kicked off in six Brazilian cities on Saturday.

The government is spending more than $3 billion on stadiums, some of them obvious white elephants but it hasn’t carried out many of the essential public transportation projects it promised.

One of the challenges facing the movement’s leaders is articulating a message beyond that of, ‘We want better treatment and more rights.’ And until they do that it will struggle to achieve anything concrete.

Anyone who has spent any time in Brazil knows that people are treated abysmally. As I said here last week, Brazilians pay first world taxes and get third world services. No one respects no one. Complaining is futile and the deck is heavily stacked against anyone who raises their voice in anger. (Which is one of the reasons a more generalized outrage hasn’t taken hold until now.)

Brazil deserves great credit for lifting 40 million people out of poverty over the last decade. But ironically, that class of newly enfranchised people might be a cause of the unrest.

– More people can afford to buy cars and hundreds of new cars pour onto the streets of Sao Paulo each day. But the government hasn’t invested in infrastructure like roads or highways and public transport is underfunded and inefficient and an unappealing alternative.

– More people can afford health insurance but the companies selling them not only provide a risible coverage, they fight tooth and nail to stop their clients from getting the treatment they are paying for, sometimes with tragic consequences.

– More people have cable television but just try calling up and complaining about the service or trying to cancel it. The companies sadistically force their clients to jump through online hoops in order to hold them to costly contracts.

– More people have cell phones and Brazilians pay some of the highest rates in the world. But calls frequently cut out, the signal is patchy, and after sales service is a joke.

– More people have banks accounts but banks charge abusive interest rates – 237 % a year for credit cards – and they sneak additional charges onto bills, and treat customers more like waling wallets than valued customers.

– Education is a joke. A tragic joke.

In short, there are lots of reasons why Brazilians should be angry.

The other big question is how politicians will deal with the crisis. What possible answers can they provide? Not only are they discredited, they cannot hope to provide quick solutions to resolve long-standing infrastructure issues.

They are in bed with the multinationals and conglomerates whose consistent mistreatment of and disdain for their customers is a complaint I hear every single day from Brazilians.

It is hard to see how they can provide quick and satisfactory answers to the questions above.

And last but not least, Are Brazilians going to see this through to the end?

Brazil is not a politicised society nor one where memories are long or protests lasting. In neighbouring Argentina, hundreds of thousands of people take to the streets to protest graft and they do it again and again and again.

Brazil’s media will play up the violence and they will play up the fear. If political parties try to hijack the movement it will lose its credibility. The middle class must get involved and stay involved.

If Brazilians really want to see change they will need stamina and resolve. They may have to shout themselves hoarse over and over and over again. If this is really going to turn into something lasting then Monday night is not the end. It is only the beginning.

Brazil is not a country where people protest. It is not a country of revolutionaries.

As Mauricio Savarese explains in this clear and didactive blog, Brazilians abhor violence and they avoid it all costs. If your cause embraces violence then you’ve lost. The only way to win in Brazil – and that means by getting the larger public behind you – is through peaceful protest and negotiation.

That’s one of the reasons the reaction to last Thursday’s protest and police violence in Sao Paulo are so interesting.

Lots of people are asking whether this wave of protests can really be over a 20 centavo rise in bus fares. (20 centavos is about 10 cents or 7 pence.)

Phillip Vianna in this CNN blog says “it is the uprising of the most intellectualized portion of society.” Marcelo Rubens Paiva in today’s Estado de Sao Paulo says the protests are “a collective revolt against the state that treats individuals as a nuisance, the enemy.” And the RioReal blog suggests that “the twenty centavos could represent a tipping point in Rio’s general panorama, as citizens wake up to authoritarian government and a longtime lack of dialogue.”

I’d love them to be right. Rubens Paiva’s definition of how the state treats its citizens is certainly spot on.

Brazilians pay first world taxes and get third world services in return. Their politicians represent big interests and treat voters with little more than contempt. Corruption is ingrained, a part of the country’s culture and fabric.

No one protests. No one gets angry. Anti-corruption demonstrations rarely unite more than a few thousand people. (Clicking a button on facebook doesn’t count as anger, or protest.)

Brazilians can’t be bothered taking to the streets because they know that unless the protests gain nationwide scope they will be ignored. And they know that won’t happen because most people don’t see the point. It’s a vicious circle. “Why bother demanding change; nothing changes so why bother.”

But there’s an awful lot of wishful thinking going on in some of the analysis. It is way too early to say last week’s protests mark a turning point. They could very easily peter out. If there is more violence then support will erode and the protesters will be marginalised.

Is this the start of something? Are Brazilians waking up? Have they finally decided enough is enough?

I certainly hope so and I do think it is inevitable, sooner or later. As incomes grow, people will start demanding better treatment.

When enough Brazilians can make the trip to Miami and see they can buy a white tshirt in GAP for $8 dollars, rather than pay $30 for the same inferior quality garment in Sao Paulo and Rio they might be shaken into action. Last week’s protests might be the first sign of that.

But I am not convinced that moment has arrived.

A lot will depend on the character of the next week’s protests. If they are hijacked by the same extremists, who often glob onto anything anti- then they will fail. The middle class will take fright and abandon them. And without middle class lending their voice en masse they are doomed.

If they can get lots of people out on the streets, from all sectors of society, and if they can demonstrate peacefully, even in the face of police provocation, then they might be on to something and the optimistic predictions of a paradigm shift might be realised.

Next week is going to be very interesting.

I just got home after wandering around the streets near my home and I have to say that of all the thousands of nights I’ve spent in Brazil, this was one of the more remarkable.

Not just because there are police helicopters overhead in my normally gentile neighbourhood. Not just because the main roads are blocked with burning rubbish. And not even because there is tear gas in the air and periodic bangs caused by the police firing off shock bombs and rubber bullets.

It’s all that. But what I really can’t believe is Why? Or rather How. How did things get so bad so fast? How did the state and municipal governments, and most importantly the police, let it get to this?

This is a protest over a small hike in bus fares that went into effect a week ago.

I won’t go into the rights or wrongs of the fare rise – from 3.00 reais to 3.20 reais – as I don’t know enough about it. (Although I will say that protesters demanding free public transport for all are living in cloud cuckoo land.)

But what has become crystal clear tonight, even through the haze of tear gas, is that the Sao Paulo government has once again overreacted with a breathtaking brutality and incompetence. They never learn.

The police are military police and therein lies one of the main problems. Historically unprepared to deal with dissent and opposition and untrained to meet the demands of a democratic society, their first response is to reach for their batons or their guns.

I won’t get into any of the other cases in which Sao Paulo police officers have been accused of brutal overreaction. (But here’s three links to cases where they are accused of murder, here, here and here.)

The fact is that with a modicum of common sense and leadership from state and municipal authorities, tonight’s protest would probably have passed fairly peacefully.

The overwhelming majority of protesters were non-violent. They even chanted “Sem Violencia!” (No Violence!) But even if there were a few troublemakers (and that’s not unlikely) it wouldn’t justify such a heavy handed response.

Basic common sense dictates that unless protests are violent you sheperd protesters away from sensitive areas. You let them have their say and then wait for them to go home. You don’t send in the riot police, the cavalry, and fire tear gas and rubber bullets at unarmed students.

What are these people thinking? Who was giving the orders? And perhaps most importantly, will they learn from their mistakes?

I am not holding my breath….

Corinthians issued a statement this afternoon saying it would only allow TV cameras and press into tomorrow’s game against Millonarios if Conmebol called them and expressed permitted it.

According to Corinthians, the club doesn’t know if the ban on fans includes “authorities, those invited by federations, the local mayor’s office, and the Pacaembu, or over 60s and under 12s, and the press.”

It seems like a transparently infantile attempt by the Libertadores champions to cock a snook at Conmebol, who imposed the ban after a flare fired by a Corinthians fan killed a 14-year old Bolivian supporter at last week’s game vs. San Jose.

Fans are regularly banned from stadiums. TV cameras are always allowed in. In no case I can ever remember has the definition of fans only included those between 12 and 60 years of age.

Conmebol’s sanction is harsh and arbitrary and Corinthians should work to reduce it.

But the club should let TV, radio and newspapers in. To stop them on such flimsy grounds is an insult to the fans who want to see, hear and follow their team.

I almost went to a balada this weekend but instead arrived home early having went through one of those small but telling experiences that reinforce my belief Brazil is still a long way from ever fulfilling its true potential.

I arrived at the door to the Trackers club around 1 am with half a dozen friends, both foreign and Brazilian. Voodoo Hop, an otherwise admirable group that seeks to rejuvenate the city centre by running clubs and cultural events in abandoned buildings, were organising another of their successful club nights.

After waiting half an hour to edge up the queue and get in the door, we discovered that there was another queue inside the building to get into the actual club.

My friends – most of whom were a good deal younger than me – took it in their stride. I was outraged. After another 10 minutes waiting in the second queue that snaked up two flights of stairs, I left.

Brazil has problems with lots of things that won’t change overnight. Corruption, antiquated infrastructure, a putrid political system, and the obscene amount of power leveraged by multinationals and construction companies are all ingrained in the culture and will only improve with government intervention or massive pressure from society, neither of which looks like happening any time soon.

But the stupid invention of bureaucracy for simple tasks like getting in a night club is easy to resolve. One queue, fine. Two queues, pointless and self-defeating.

The big worry I have here – and this is the part that reinforce my belief Brazil is still a long way from fulfilling its potential – is that I was the only one who saw anything wrong with this.

Not only were the organizers of this young and hip nightclub happy to carry on with the same old bureaucratic and non-sensical rules imposed on them by an older generation. (If there’s a good reason from this, I’d be happy to hear it, VoodooHop…)

What was worse was that the young kids waiting in line accepted it as normal. There was no outrage at being made to stand passively in two different queues, much less being made to stand passively in two different queues for the right to hand over a 30 real entry fee.

Instead, anyone who complained was “uptight”, “stressed out” or “whining.”

I voted with my feet. Unless more people do the same, the bureaucracy and BS is never going away.

Here’s a nice little idea to encourage people to go to football matches, courtesy of the the Museu de Futebol, already one of the best places to visit in São Paulo.

Present your match ticket from any Paulista stadium at the door and get entry for only 2 reais. (Normal entry fee is 6 reais.) One game days, tickets will be sold for 4 reais.

The museum is also making it easier to visit on game days. The museum is built into the Pacaembu stadium, home to Corinthians and where Santos and Palmeiras also play regularly.

It is now going to open up until two hours before kick-off on game days.

The museum is fantastic and well worth a visit, even if it does lack content in English.

I went to see Fernando Haddad celebrate his election in Sao Paulo last night and I came away with one sincere wish – that his government is better organised than his victory party.

The event at the Intercontinental Hotel was among the worst organised I’ve ever been to and a slap in the face to the party faithful who were prevented from seeing him give his victory speech because Workers’ Party ‘organisers’ placed banks of TV cameras in front of them.

There was no room for journalists, who were so tightly packed into spaces at the side of the hall that one woman fainted.

The sound system was poor and the noise from the party faithful – who, unable to see the event they had worked so hard to make happen, chatted away over his speech – made it hard to hear.

Anyone who’s ever been to a major event knows how to set up something like this. TV cameras at the very back on a raised platform. Seats for the press in front of them. If there are dignitaries, like there were yesterday, they sit closest to the stage.

It’s not rocket science.

The most depressing thing about this isn’t only the lack of respect shown to so many people. (The only ones treated halfway decent were party big-wigs and allies such as Paulo Maluf who sat out front.)

It is that no one ever seems to learn. These people must have been to big events before, they must have seen other people organise such things competently. How hard is it to take that on board?

One of the reasons Haddad won the election was because Paulistanas are sick and tired of the incompetency, arrogance and lack of respect shown by current Mayor Gilberto Kassab. They desire a city that is functioning, equitable, clean and well run.

Haddad campaigned on a platform of Change and his slogan last night was “The Future Won.”

The victory party was an embarrassment. If that is the kind of organisation we get from his government, we’re in for a rough four years.

Great blog post on The Economist website today about Brazil’s planned $17 billion bullet train.

Brazil has been talking about this for years but plans have yet to get off the drawing board. No one wants to take on the challenge because they don’t think it’s an economically viable project.

The Economist piece takes a while to get to the point, which is this. And I quote:

“Most of Brazil’s roads are unpaved. Some important routes—including some interstate highways—are single-lane and extremely dangerous. Half the population is not connected to the sewage system. There are few (ordinary) commuter or freight rail lines, and they are mostly in very poor condition. Urban mass transport is grossly deficient: São Paulo, a metropolis of nearly 20m souls, has a mere 71km (44 miles) of metro, plus a few overland urban rail lines, which at peak hours are all terrifyingly overcrowded. It is so easy to think of a long list of more worthwhile infrastructure projects in Brazil that it is hard to understand why this one is not dismissed out of hand.”

I’d put it more succinctly:

The plan to spend at least 34 billion reais (and probably much more) on the bullet train is a classic example of Brazil’s delusions of grandeur. Brazil has hardly any rail system and yet wants to build a high speed train link. It has hardly any submarines and yet plans to build a nuclear sub. It has just published plans for its 4G network when its 3G doesn’t work properly.

Brazil should be concentrating on walking before it can run. It has taken laudable steps to reduce inequality but there is so much more to be done to make life liveable for the poorest sectors of society and those should take precedence over Pharaonic projects like a bullet train.

Why is it doing this? Who knows. It wants to be first world. It wants to show off. It wants to show it can. It’s not because it needs it.

So why do it? Not for consumers or passengers. As The Economist suggests, the number of passengers is likely to be half the government’s estimate and prices are likely to be double.

Who benefits? That one’s easier to answer. The same corrupt kleptocrats in the political class and their bosom buddies who run the construction companies.