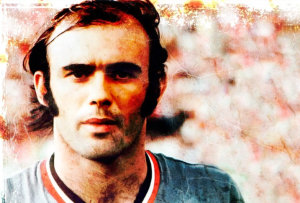

It is unfortunate that Waldir Peres, the Brazilian goalkeeper who died on Sunday aged 66, will be remembered mostly for his calamitous mistake in the 1982 World Cup match against the USSR.

Arquivo Histórico do São Paulo FC

Peres let Andrei Bal’s 30-yard strike squirm through his hands and the image became an unforgettable one for fans, particularly those outside Brazil, who thought of Brazilian goalies as no less dodgy than Scottish ones.

Peres was widely seen as the weak link in that star-studded team, alongside misfiring centre forward Serginho.

But Peres’ team mates did not agree with that assessment.

Sócrates was not close to Peres, who was older than he was and as a happily married homebody, not part of Sócrates’ drinking circle. The two also differed over Corinthians Democracy, with Peres and his team mates at São Paulo often dismissive of what they considered a distraction to the sole issue of playing football.

But Sócrates refused to condemn Peres for his mistake or single him out as a weak link. He pointed out that Peres was the best keeper in Brazil in the lead up to the 1982 World Cup and deserved his place.

Most notably, he had proved his worth in the 1981 mini-tour to Europe. Brazil beat France, West Germany and England and Peres was a factor in all three.

He saved not one but two penalties from Paul Breitner in the 2-1 win over West Germany that cemented Brazil’s position as favourites to lift their fourth World Cup title a year hence in Spain.

He was then excellent in the 1-0 victory over England at Wembley, a victory notable as the first time England had ever lost to a South American side at home.

Peres got his spot in fortunate circumstances, after first-choice stopper Carlos injured his elbow in the Mundialito tournament in Uruguay. Peres stepped in and helped Brazil to the final, defeating West Germany 4-1 in the process, before losing to the hosts.

But his performances helped cement his place, as did his personality.

He was quiet and serious and easy to get along with, unlike Emerson Leão, his other main rival for the No. 1 shirt. Leão had been first choice in 1974 and 1978 but seemed to enjoy rubbing people up the wrong way and coach Telê Santana refused to pick someone who would so obviously endanger the bubbly spirit in what was a settled and contented side.

After that early error against the USSR, Peres composed himself and performed well. He had little do against Scotland or New Zealand and was reliable in the 3-1 win over Argentina in the second round.

He was also blameless in the fateful 3-2 loss against Italy. Brazil went out not because of goalkeeping errors but because they kept trying to win a game they only needed to draw. They were exposed at the back and only the harshest of critics could fault him for any of Paolo Rossi’s three goals.

Unfortunately for Peres, those incidents are forgotten now. But the facts speak for themselves. He won the Brazilian league title with São Paulo and three Paulista state championship medals. Only one player in the clubs history has more appearances that he has.

He is fondly remembered at São Paulo. He deserves to be known elsewhere for more than that one mistake.

This is the only book on the list that I haven’t read but I want to recommend it for the simple reason that it offers an entirely different perspective on Brazilian football than all the others. Written by an 18-year old English lad who came to Brazil for a youth tournament and was signed up by a small side in the provinces, it promises a ‘bittersweet look at the beautiful game,’ as well as what is teasingly called its ‘dark side.’ It’s on my list of books to read.

This is the only book on the list that I haven’t read but I want to recommend it for the simple reason that it offers an entirely different perspective on Brazilian football than all the others. Written by an 18-year old English lad who came to Brazil for a youth tournament and was signed up by a small side in the provinces, it promises a ‘bittersweet look at the beautiful game,’ as well as what is teasingly called its ‘dark side.’ It’s on my list of books to read. This is a book about the origins of Brazilian football, and particularly the British influence on those early days. Everyone knows the story of Charles Miller, arriving at the port of Santos in 1894 with a ball and a rule book, but there were many other key figures, and not just players. Hamilton painstakingly researches the administrators and referees as well and shows just how they influenced football in its early days in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. The book has valuable biographical info about Miller and is filled with interesting details and stories tying the UK and Brazil as football started to emerge as a global game.

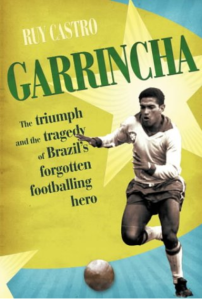

This is a book about the origins of Brazilian football, and particularly the British influence on those early days. Everyone knows the story of Charles Miller, arriving at the port of Santos in 1894 with a ball and a rule book, but there were many other key figures, and not just players. Hamilton painstakingly researches the administrators and referees as well and shows just how they influenced football in its early days in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. The book has valuable biographical info about Miller and is filled with interesting details and stories tying the UK and Brazil as football started to emerge as a global game. Off the field, Garrincha’s life was a mix of triumph, comedy, soap opera and tragic farce. A winger for Botafogo who spent most of his life married to one of Brazil’s most famous samba stars, Garrincha died aged just 50 from complications caused by acute alcoholism. The book is absolutely packed with stories from that immense life and the entertainment is doubled with stories of his footballing glories. And there were many. Garrincha was the equal of Pelé to many Brazilians – certainly he was more beloved as a personality – and he won two World Cup winner’s medals. The highs and the lows are all here and they make for sensational reading. (Full disclosure: I translated it from Portuguese to English.)

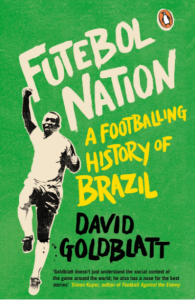

Off the field, Garrincha’s life was a mix of triumph, comedy, soap opera and tragic farce. A winger for Botafogo who spent most of his life married to one of Brazil’s most famous samba stars, Garrincha died aged just 50 from complications caused by acute alcoholism. The book is absolutely packed with stories from that immense life and the entertainment is doubled with stories of his footballing glories. And there were many. Garrincha was the equal of Pelé to many Brazilians – certainly he was more beloved as a personality – and he won two World Cup winner’s medals. The highs and the lows are all here and they make for sensational reading. (Full disclosure: I translated it from Portuguese to English.) Goldblatt is a brilliant researcher and historian, and after writing what are considered to be the definitive histories of both football and the Olympics he turned his hand to Brazil ahead of the 2014 World Cup. Like Bellos’ book, the focus here is not the games or the clubs or the players, it’s how football developed in South America’s most dynamic nation. Goldblatt has a gift for taking a dry topic like the construction of a new capital city and mixing it with football to make it more readable. He does that with several different subjects and eras, allowing readers to learn about Brazil’s art, literature, culture and politics, almost without noticing.

Goldblatt is a brilliant researcher and historian, and after writing what are considered to be the definitive histories of both football and the Olympics he turned his hand to Brazil ahead of the 2014 World Cup. Like Bellos’ book, the focus here is not the games or the clubs or the players, it’s how football developed in South America’s most dynamic nation. Goldblatt has a gift for taking a dry topic like the construction of a new capital city and mixing it with football to make it more readable. He does that with several different subjects and eras, allowing readers to learn about Brazil’s art, literature, culture and politics, almost without noticing. If you only read one book about Brazilian football this is the one. This is not specifically about the great players or the great games. But you will come away from this with a wide and fascinating knowledge of why Brazilians love football and what makes the game such an important facet of life here. The book touches on diverse subject like how Portuguese is shot through with footballing vocabulary, why so many Brazilians play overseas, and why locals prefer Garrincha to Pelé. It’s also great fun to read and pretty much timeless.

If you only read one book about Brazilian football this is the one. This is not specifically about the great players or the great games. But you will come away from this with a wide and fascinating knowledge of why Brazilians love football and what makes the game such an important facet of life here. The book touches on diverse subject like how Portuguese is shot through with footballing vocabulary, why so many Brazilians play overseas, and why locals prefer Garrincha to Pelé. It’s also great fun to read and pretty much timeless.